Ciampitti leads modern, complex research

It does not take a long conversation with Dr. Ignacio Ciampitti to understand how much he values being people-centric. Yet, it is easy to talk at length with the Kansas State University Agronomy professor and researcher as he discusses projects on the docket in the Ciampitti Lab.

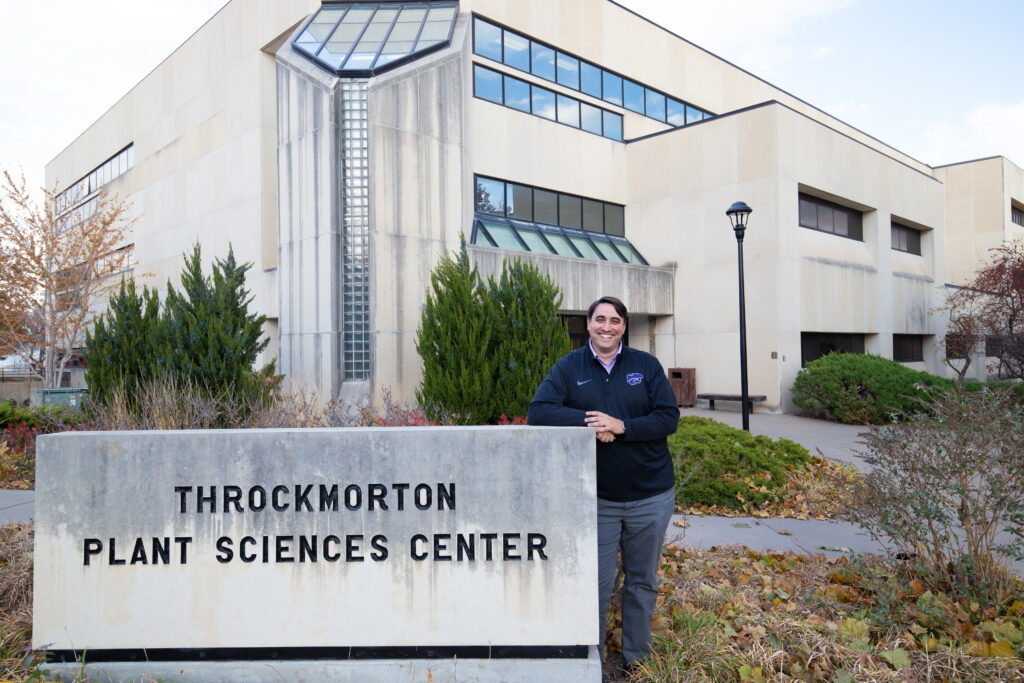

The lab setting is a modest room on the inner corridors of Throckmorton Hall at K-State. There, students work diligently to study crop samples collected from various soybean states. On a particular day in November, the students quantify levels of nitrogen in seed tissues to determine how much came out of the atmosphere versus the soil. It is part of a project funded by the Kansas Soybean Commission and North Central Soybean Research Program that studies soybean quality and various conditions that affect such a value.

The research rolls nitrogen fixation, sulfur fertilization, planting dates and dry down conditions into one seed quality analysis to generate a dataset and ultimately inform the creation of decision-making tools.

“The project is complex because, as any farmer knows, there are multiple factors [in the field],” Ciampitti says. “One of the key components is trying to understand how much nitrogen the plants are really fixing and how much of the nitrogen is coming from the soil. We want to understand this for a couple reasons – we want to make sure the plant can always be competitive and yield well, and we also want to make sure the plants are yielding well years down the road.”

He explains that as much as 70 percent of the nitrogen in a soybean crop is taken out of the field at harvest. To maintain a neutral “nitrogen budget,” the plants must fix an amount equal to what was previously removed. Existing research indicates applying nitrogen fertilizer to soybeans prompts little to no response, putting emphasis on the ability for soybeans to fix available nitrogen. Ciampitti’s project looks to determine methods to boost the fixation process to continually make up for what is lost.

“For me, trying to understand the fixation process and see how we can help it is critical for thinking about long-term productivity and sustainability of the crop,” he says. “There are multiple uses of soybeans in the market, and we want to make sure we have enough supply for the future.”

According to the project description, surprisingly little is known about the amounts of nitrogen fixed by soybeans. That prompts many questions about the amount of the element removed with high-yielding soybeans – or in stressful environments – and whether the soil reserves can keep up. One potential solution to boosting nitrogen fixation could be sulfur fertilization.

“One of the key factors we are looking at is sulfur,” Ciampitti shares. “Sulfur, or the lack of, could be impacting the ability of the soybean plant to fix nitrogen.”

He explains that symptoms presenting as a nitrogen deficiency in soybeans could really be an issue with the sulfur levels, which would be much more simple to solve. It is an example of how one factor in the field can impact another and ultimately impact yields, he says.

Yields are also susceptible to changes in the seed filling and dry-down stages of soybean growth. This adds another layer to Ciampitti’s project. He explains that soybean seeds lose three to four percentage points of moisture each day from 60 percent moisture at the time the plant reaches maturity to an ideal 13 percent at the time those seeds should be harvested. It is difficult, however, to be in the field on the exact day moisture reaches the ideal threshold. A few days too late could mean dollars lost.

To manage the dry-down stage, Ciampitti envisions a prediction tool that helps farmers prioritize their fields. To get there, interdisciplinary work with weather scientists and other experts is vital, he says, because it would connect weather data with crop data in a format that is practical for farmers.

The next layer of the project studies how various crop conditions impact crop nutrition. Protein content and yield tend to have an inverse relationship, Ciampitti says. As yield accumulates, energy within the plant produces carbohydrates first.

“The nitrogen fixation aspect of the project is important to me because I care about the productivity of farmers and making sure that our soybean production is sustainable,” Ciampitti shares. “The quality aspect of the project is important because I care about farmers getting more value for their crop in the future.”

He says the industry often overlooks quality in lieu of productivity. The U.S. has reached a good level of productivity, he adds, and can begin to identify the best practices to manage high-quality soybeans. So far, the team has collected data from over 200 fields across two years to track what those practices are. The emphasis on protein quality in the current study and being more precise in identifying “protein hotspots” within fields could tap into a whole new premium for soybeans. He believes they can utilize science to get ahead of the market.

Ciampitti approaches all research with forward thinking, saying, “I feel that, as a university, part of our role is to help farmers think toward the future. I want to ensure if I am working with the checkoff or industry that we are being innovative. There are going to be more and more challenges to address.”

Feedback from farmers is vital in the success of Ciampitti’s research projects year after year. He shares that he tries to keep the research relevant and relies on conversations with farmers to guide new research ideas and proposals. Ciampitti and members of his team are in contact with farmers every week and utilize Extension events to make connections.

“By just listening to farmers, you start to think about how you can solve those problems they face,” he says. “You think for each scenario how to manage the crop better. We don’t need to be perfect; we just need to be better. We move one step forward any time we do a research project.”

Ciampitti says his passion was always to discover ways to help farmers, all the way back to his early life in Argentina. He has roots in farming and earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in agronomy and soil science, respectively, at the University of Buenos Aires. Following his doctoral studies in crop physiology and plant nutrition at Purdue University, Ciampitti landed at K-State in 2013.

It was at K-State that the Ciampitti Lab was created. Tenets of the lab, according to Ciampitti, are keeping it people-centered and allowing students to feel a sense of independence much like they would find out in the industry. The students are hand-selected to create a connected and creative space for the team to work on applied research.

“Our goal at the end of the day is to create more value for farmers and position soybeans as a crop that can generate more revenue,” Ciampitti concludes.